Every experienced Node.js developer has been there. An application runs smoothly in development, but under the strain of production traffic, a mysterious performance bottleneck appears. The usual toolkit of console.log statements and basic profilers points to no obvious culprit in the application logic. The code seems correct, yet the application slows to a crawl. In these moments, it becomes clear that the problem isn’t just what our code does, but how Node.js is executing it. This is where a surface-level understanding is no longer enough. To solve the hard problems and build truly high-performance applications, we need to look under the hood.

The V8 Engine – The Turbocharged Heart of Execution

While we write our applications in JavaScript, the computer’s processor doesn’t understand functions or objects. It understands machine code. The task of bridging this gap falls to the V8 JavaScript Engine, the same high-performance engine that powers Google Chrome. V8’s primary job is to take our JavaScript and compile it into optimized machine code at lightning speed, making Node.js applications not just possible, but incredibly fast. To achieve this feat, V8 employs a series of sophisticated strategies, beginning with its core component: the Just-In-Time (JIT) compilation pipeline.

The JIT (Just-In-Time) Compilation Pipeline

At the core of V8’s performance is a sophisticated Just-In-Time (JIT) compilation strategy. Instead of fully compiling all JavaScript to machine code before running it (which would be slow to start) or interpreting it line-by-line (which would be slow to run), V8 does both. This process involves a dynamic duo: a fast interpreter named Ignition and a powerful optimizing compiler named TurboFan.Let’s explore this pipeline through the lens of a car rental application. When our Node.js server starts, it needs to be ready for requests immediately. This is where Ignition, the interpreter, shines. Imagine a function that calculates the base cost of a rental:

function calculateBasePrice(car, days) {

// A simple price calculation

return car.dailyRate * days;

}

When this function is defined and first called, Ignition acts like a simultaneous translator. It doesn’t waste time with deep analysis; it quickly converts the JavaScript into bytecode—a low-level, platform-independent representation of the code. This allows our application to start handling rental price calculations almost instantly. The translation is fast, but the resulting bytecode isn’t the most efficient code possible; it’s a general-purpose version designed for speed of execution startup, not raw performance.Now, imagine our car rental application becomes a hit. The calculateBasePrice function is being called thousands of times a second as users browse different cars and rental durations. V8’s built-in profiler is constantly watching and identifies this function as “hot”—a prime candidate for optimization. This is the cue for TurboFan, the optimizing compiler, to step in. TurboFan is like a master craftsman who takes the generic bytecode produced by Ignition and forges it into highly specialized, lightning-fast machine code. It does this by making optimistic assumptions based on its observations. For example, it might notice that in 99% of calls to calculateBasePrice, the car object always has a dailyRate property that is a number, and days is also always a number. Based on this, TurboFan generates a version of the function tailored specifically for this scenario, stripping out generic checks and creating a direct, high-speed path for the calculation.But what happens when those assumptions are wrong? This is where the crucial safety net of Deoptimization comes into play. Let’s say a new feature is added to our application for weekend promotions, and a developer now calls the function like this:

// The optimized code expects 'days' to be a number

calculateBasePrice({ dailyRate: 50 }, "weekend_special");

The highly optimized machine code from TurboFan hits a snag; it was built on the assumption that days would be a number, but now it has received a string. Instead of crashing, V8 performs deoptimization. It gracefully discards the optimized code and falls back to executing the original, slower Ignition bytecode. The generic bytecode knows how to handle different data types, so the program continues to run correctly, albeit more slowly for this specific call. This process is a performance penalty, but it ensures correctness and stability, allowing V8 to be incredibly fast most of the time while safely handling unexpected edge cases.

Hidden Classes (or Shapes)

While the JIT pipeline provides a macro-level optimization strategy, V8’s speed also comes from clever micro-optimizations. One of the most important is the use of hidden Classes, also known as Shapes. Because JavaScript is a dynamic language, the properties of an object can be added or removed on the fly. For a compiler, this is a nightmare. If it doesn’t know the “shape” of an object, it has to perform a slow, dictionary-like lookup every time you access a property like car.model.To solve this, V8 creates an internal, hidden “blueprint” for every object structure it encounters. Objects that have the same properties, added in the same order, will share the same hidden class. This allows V8 to know the offset of each property in memory. Instead of searching for the model property, it can simply access the memory location at, for example, “object address + 24 bytes.” This is orders of magnitude faster.The performance implications of this are significant and directly influence how you should write your code. Consider this suboptimal approach in our car rental application, where we create two car objects.

// Bad Practice: Creating objects with different property orders

// Car 1

const car1 = { make: 'Honda' };

car1.model = 'Civic';

car1.year = 2022;

// Car 2

const car2 = { model: 'Corolla' };

car2.make = 'Toyota';

car2.year = 2023;

Even though car1 and car2 end up with the same properties, they were added in a different order. From V8’s perspective, they have different “shapes” and will be assigned different hidden classes. Any function that operates on these objects cannot be fully optimized, as V8 can’t rely on a single, predictable memory layout.Now, let’s look at the optimized approach. By initializing our objects consistently, we ensure they share the same hidden class from the moment they are created. The best way to do this is with a constructor or a factory function.

// Good Practice: Ensuring a consistent object shape

function createCar(make, model, year) {

return {

make: make,

model: model,

year: year

};

}

const car1 = createCar('Honda', 'Civic', 2022);

const car2 = createCar('Toyota', 'Corolla', 2023);

In this version, car1 and car2 are guaranteed to have the same hidden class. When TurboFan optimizes a function that processes these car objects, it can generate highly efficient machine code that relies on this stable shape, leading to a significant performance boost in hot code paths. Writing shape-consistent code is one of the most powerful yet simple ways to help V8 help you.

Inline Caching

Establishing stable object shapes with Hidden Classes is the foundation for another critical V8 optimization: Inline Caching (IC). If Hidden Classes are the blueprint for an object’s memory layout, Inline Caching is the high-speed assembly line that uses that blueprint. It dramatically speeds up repeated access to object properties.Think of it like a speed-dial button on a phone. The first time you call a new number, you have to look it up in your contacts, which takes a moment. If you know you’ll call that number often, you save it to speed-dial. The next time, you just press a single button. Inline Caching works on the same principle.Let’s see this in our car rental application. Imagine a function that is called frequently to display a car’s summary to a user.

function getCarSummary(car) {

return `A ${car.year} ${car.make} ${car.model}.`;

}

const car1 = createCar('Honda', 'Civic', 2022);

// First call to getCarSummary

getCarSummary(car1);

getCarSummary is called, V8 has to do the “lookup.” It examines car1, sees its hidden class, and determines the memory offset for the year, make, and model properties. This is the slow part. However, V8 makes an assumption: “The next object passed to this function will probably have the same hidden class.” It then “caches” the result of this lookup directly within the compiled code.When the function is called again with an object of the same shape, the magic happens.

const car2 = createCar('Toyota', 'Corolla', 2023);

// Subsequent calls

getCarSummary(car2); // This is extremely fast

getCarSummary(car1); // So is this

year property is at offset +16, make is at offset +0, and model is at offset +8.” It can retrieve the values almost instantly. When this happens in a loop that runs thousands of times, the performance gain is immense. This is known as a monomorphic state—the cache only has to deal with one object shape, which is the fastest possible scenario.The system is smart enough to handle a few different shapes (a polymorphic state), but if you pass too many different object shapes to the same function, the inline cache becomes overwhelmed (a megamorphic state) and the optimization is abandoned. This is why the advice from the previous section is so crucial: writing code that produces objects with a consistent shape is the key that unlocks the powerful performance benefits of Inline Caching.

libuv – The Unsung Hero of Asynchronicity

If V8 is the engine of a high-performance car, then libuv is the sophisticated transmission and drivetrain that puts the power to the road. It’s the component that gives Node.js its defining characteristic: non-blocking, asynchronous I/O. A common misconception is that Node.js is purely single-threaded. While your JavaScript code does indeed run on a single main thread, libuv quietly manages a pool of background threads to handle expensive, long-running tasks like reading files from a disk or making network requests.

Imagine our car rental office. The front-desk clerk is the main JavaScript thread. They can only serve one customer at a time. If a customer wants to rent a car and the clerk has to personally go to the garage, find the car, wash it, and bring it back, the entire queue of other customers has to wait. This is “blocking” I/O. Instead, the Node.js model works differently. The clerk takes the request, then hands it off to a team of mechanics in the garage (the libuv thread pool). The clerk is now immediately free to serve the next customer. When a mechanic finishes preparing a car, they leave a note for the clerk, who picks it up and notifies the correct customer. The mechanism that orchestrates this efficient hand-off is the Event Loop.

The Event Loop: A Detailed Tour

The Event Loop is not the simple while(true) loop it’s often portrayed as. It is a highly structured, multi-phase process managed by libuv, designed to process different types of asynchronous tasks in a specific order during each “tick” or cycle.

The first phase is for timers. This is where callbacks scheduled by setTimeout() and setInterval() are executed. If our car rental app needs to run a check for overdue rentals every hour, the callback for that setInterval would be a candidate to run in this phase, once its designated time has elapsed.

Next come pending callbacks. This phase executes I/O callbacks that were deferred to the next loop iteration, typically for specific system-level errors. It’s a more specialized phase that you won’t interact with directly very often. After this are the internal idle and prepare phases, used only by Node.js itself.

The most critical phase is the poll phase. This is the heart of I/O. When our application needs to fetch car availability from the database or read a customer’s uploaded driver’s license from the disk, the request is handed off to libuv’s thread pool. The poll phase is where the event loop asks, “Has any of that work finished?” If so, it retrieves the results and executes the corresponding callback functions. If there are no pending I/O operations and no other tasks scheduled, Node.js may block here, efficiently waiting for new work to arrive instead of spinning the CPU uselessly.

Following the poll phase is the check phase, where callbacks scheduled with setImmediate() are executed. This is useful for code you want to run right after the poll phase has completed its I/O callbacks. For example, after processing a batch of new rental bookings from the database in the poll phase, you might use setImmediate() to schedule a follow-up task to update the general availability counter.

Finally, the close callbacks phase executes callbacks for cleanup events, such as when a database connection or a websocket is closed with a .on('close', ...) event handler.

Where do process.nextTick() and Promises fit?

A crucial point of confusion is how process.nextTick() and Promise callbacks (using .then(), .catch(), or async/await) fit into this picture. The answer is: they don’t. They are not part of the libuv event loop phases. Instead, they have their own special queue called the microtask queue. This queue is processed immediately after the currently executing JavaScript operation finishes, and before the event loop is allowed to proceed to its next phase.

This has a profound impact on execution order. A nextTick or Promise callback will always execute before a setImmediate or a setTimeout callback scheduled in the same scope.

Consider this code in our rental application:

const fs = require('fs');

fs.readFile('customer-agreement.txt', () => {

// This callback runs in the POLL phase

console.log('1. Finished reading file (I/O callback)');

setTimeout(() => console.log('5. Timer callback'), 0);

setImmediate(() => console.log('4. Immediate callback'));

Promise.resolve().then(() => console.log('3. Promise (microtask)'));

process.nextTick(() => console.log('2. Next Tick (microtask)'));

});

When the file is read, its callback is executed in the poll phase. Inside it, the microtasks (nextTick and Promise) are scheduled. They will run immediately after the file-read callback finishes, but before the event loop moves on. The setImmediate is scheduled for the check phase of the same loop tick, and the setTimeout is scheduled for the timers phase of the next loop tick. The output will reliably be:

1. Finished reading file (I/O callback)

2. Next Tick (microtask)

3. Promise (microtask)

4. Immediate callback

5. Timer callback

Understanding this distinction is the key to mastering Node.js’s asynchronous flow and debugging complex timing issues.

The C++ Layer – The Bridge Between Worlds

We have seen how V8 handles our JavaScript and how libuv manages asynchronicity. The final piece of the puzzle is understanding how these two distinct worlds communicate. V8 is written in C++ and understands things like objects and functions. Libuv is a C library that understands system-level concepts like file descriptors and network sockets. The critical link between them is a layer of C++ code within Node.js itself, often referred to as the bindings. This layer acts as a bilingual interpreter, translating requests from JavaScript into a format libuv understands, and then translating the results back.

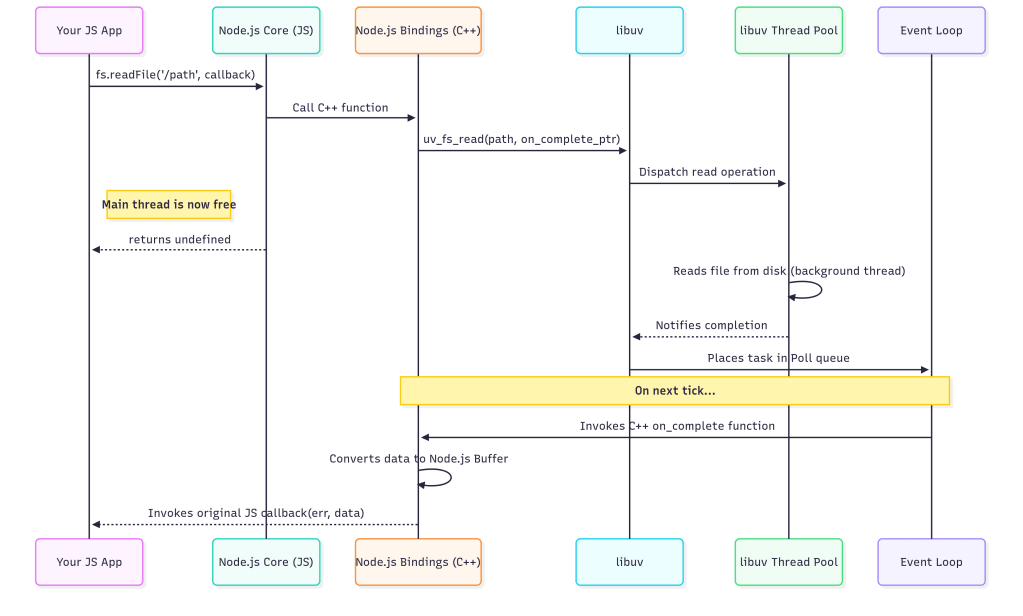

To truly grasp this, let’s trace the complete lifecycle of one of the most common asynchronous operations: fs.readFile. Imagine in our car rental application, a user has just uploaded an image of their driver’s license, and we need to read it from the server’s temporary storage.

The journey begins in your application code, with a familiar call:

const fs = require('fs');

fs.readFile('/tmp/license-scan.jpg', (err, data) => {

if (err) {

// handle error

return;

}

// process the image data

console.log('Successfully read license scan.');

});

When this line executes, the call first enters the JavaScript part of Node.js’s core fs module. Here, some basic validation happens, like checking that you provided a path and a callback function. Once validated, the call is ready to cross the bridge. It invokes a function in the C++ bindings layer. This is the first crucial translation step: the JavaScript string '/tmp/license-scan.jpg' is converted into a C-style string, and the JavaScript callback function is packaged into a persistent C++ object that can be called later.

Now in the C++ world, the binding function makes a request to libuv, asking it to read the file. It passes the translated file path and a pointer to a C++ function that libuv should invoke upon completion. At this exact moment, the magic of non-blocking I/O happens. Libuv takes the request and adds it to its queue of I/O tasks, which it will service using its background worker thread pool. The C++ binding function, and by extension, the entire fs.readFile call, immediately returns undefined. Your JavaScript code continues executing, completely unblocked. The main thread is now free to handle other requests, like processing another user’s rental booking.

Sometime later, a worker thread from libuv’s pool finishes reading the entire file into a raw memory buffer. It notifies the main event loop that the task is complete. During the event loop’s poll phase, it sees this completed task. This triggers the second half of the journey: the return trip. The event loop invokes the C++ completion function that was passed to libuv earlier. This C++ function takes the raw memory buffer and carefully wraps it in a Node.js Buffer object, which is a data structure V8 can understand. It then prepares to call the original JavaScript callback, passing the Buffer as the data argument (or an Error object if something went wrong).

Finally, the journey ends as the C++ layer invokes your original JavaScript callback function. The data parameter now holds the Buffer containing the image file, and your code can proceed to process it. The entire round-trip, from JavaScript to C++, to libuv’s worker threads, and all the way back, has happened transparently, without ever blocking the main event loop. This elegant, multi-layered architecture is the fundamental reason Node.js can handle immense I/O-bound workloads with such efficiency.

From Knowledge to Mastery

Our journey beyond console.log has taken us deep into the heart of Node.js. We’ve seen that it’s not a single entity, but a powerful trio of components working in perfect harmony. The V8 engine acts as the brilliant, high-speed mind, executing our JavaScript with incredible efficiency. Libuv serves as the tireless workhorse, managing an army of background threads to handle I/O without ever blocking the main stage. And the C++ bindings act as the essential nervous system, seamlessly translating messages between these two worlds. Together, they form a sophisticated system meticulously engineered for one primary goal: building scalable, high-throughput applications that excel at non-blocking I/O.

This knowledge is more than just academic; it’s a toolkit for writing better code. Because you now understand hidden classes and inline caching, you can structure your objects to help V8 generate faster, more optimized code. Because you can visualize the event loop phases, you can finally debug with confidence why your setTimeout seems to fire later than expected or why process.nextTick executes before setImmediate. And because you’ve traced the journey of an I/O call, you have a deep appreciation for why CPU-intensive tasks must be kept off the main thread to keep your application responsive and fast.

But don’t just take my word for it. The true path from knowledge to mastery is through experimentation. We encourage you to roll up your sleeves and see these internals in action. Fire up a Node.js process with the --trace-opt and --trace-deopt flags to watch V8’s JIT compiler work its magic in real-time. Dive into the built-in perf_hooks module to precisely measure the performance of your functions. For a powerful visual perspective, generate a flame graph of your application to see exactly where it’s spending its time. By actively exploring these layers, you will transform your understanding of Node.js and unlock a new level of development expertise.